|

Listen to this Gambling History blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Hawthorne Nevada Airlines DC-3 (N15570) on a foggy morning at Long Beach, California on November 8, 1965. This is the Gamblers Special plane that crashed four years later.

1969

A group of Southern Californians, winding down from a Monday night of gambling at the El Capitan Club in Hawthorne, Nevada, were on the “Gamblers Special” flight back home.

The plane never made it. Instead, it vanished in the wee morning darkness.

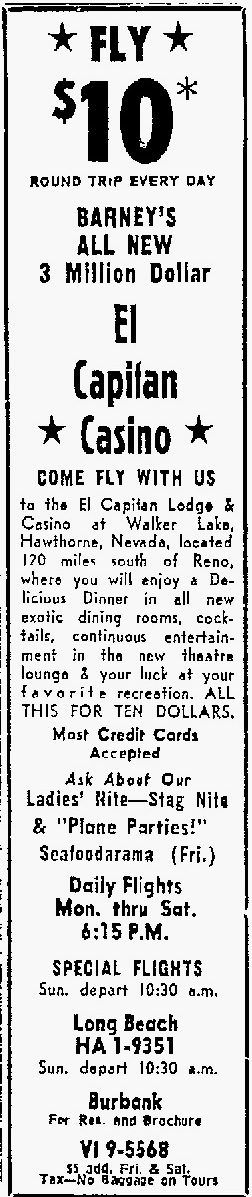

Travel ad in Long Beach’s Independent Press-Telegram, February 16, 1969

Adverse Weather Predicted

Piloted by Fred Hall, the twin-engine Douglas DC-3, carrying 32 passengers and two other crew members, left the Hawthorne Industrial Airport at 3:50 a.m. Hawthorne Nevada Airlines Flight 708 was destined for the Hollywood-Burbank Airport.

The weather forecasts for Hall’s route, which he’d navigated hundreds of times before, called for icy conditions above 6,000 feet and moderate to severe turbulence up through 15,000 feet. That night, a ferocious snowstorm dumped 40 to 50 feet of snow in the mountains over which Hall was to fly.

The Hawthorne Nevada Airlines plane was equipped with windshield and propeller anti-icing systems but no device to crack off accumulated ice mechanically, according to the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB). It also didn’t have a beeper or beacon that sends a signal when a plane hits the ground.

The last radio contact from Hall was at 4:06 a.m. with the flight service station in Tonopah, Nevada. It was February 18.

Hampered Search

Immediately, the Civil Air Patrol (CAP) began a full-scale hunt for the presumably downed aircraft along and around the flight path between Hawthorne and the Nevada’s-California border. The plane’s white color, with a blue stripe along both sides, made it even harder to spot amid the snowpack. The CAP didn’t find it.

By March 8, searchers had conducted 426 search missions, constituting 944.3 hours in the air, without success. The effort was halted. By that time, if there’d been any survivors, they likely had died.

“We’re kind of discouraged,” said Lt. Col. James Helm of the Hawthorne CAP (Reno Evening Gazette, May 5, 1969). “We just have to wait until the snow melts. We’ll find it eventually.”

Numerous pilots continued looking for the airliner in their spare time. The El Capitan Club offered a $10,000 ($71,000 today) reward to anyone who found it.

Persistence Pays Off

One of those volunteers was Stanford Pow of Bakersfield. After five months of repeated flying through the Sierra Nevada, separating coastal California from the Mojave Desert, they decided to look along the edge of the mountain range.

While cruising through that area, Pow’s wife Johnadene saw the sun glinting off of something in the snow. They suspected it was part of the aircraft but couldn’t confirm it.

Verification came the next day, Saturday, August 9, when Stanford got Eldon Fussel, his co-worker at Bakersfield’s Gold Seal Flying Service, to fly him out there in his helicopter. Fussel landed on Hogback Ridge, and the two surveyed the wreckage up close.

They saw three large plane pieces, scattered bodies and surrounding debris. All of it was on the east slope of Mt. Whitney, five miles off of the plane’s planned course.

“This is about as remote an area as you could find anywhere,” Fussel said (Nevada State Journal, Aug. 10, 1969). “There is no possibility that anyone could have lived through the crash. …it is my belief everybody aboard was killed instantly.”

It was six months since plane N15570 had disappeared.

Shift in Efforts

The Inyo County coroner and sheriff, forest service officials, and FBI and NTSB agents all got involved in recovering the plane’s passengers and investigating the crash.

Because the high-altitude terrain was too rugged for horses and two to 10 feet of snow still covered it, rescuers used two helicopters to transport the bodies to the town of Lone Pine. There, they transferred them to a vehicle and drove them to a makeshift morgue in Bishop, 60 miles away, where an FBI expert began identifying each one.

Five days later, the team had retrieved 27 of the 35 bodies. The searchers had trouble locating the remaining eight but finally did, in the fuselage remnant, the following day.

Cause and Effect

Hall had made this specific flight hundreds of times, but the winter of 1969 was severe, boasting record snowfall in the Sierra Nevada.

The NTSB indicated in its final report, following its investigation of the crash, that inclement weather had obscured Hall’s visibility, and the plane had hit “an oblong, bowl-shaped, east-west oriented canyon at a measured altitude of 11,770 feet” (Aircraft Accident Report, Feb. 4, 1970). Then it’d slid backwards about 500 feet, stopped and caught fire.

The board concluded that “the probable cause of this accident was the deviation from the prescribed route of flight, as authorized in the company’s Federal Aviation Administration-approved operations specifications, resulting in the aircraft being operated under Instrument Flight Rules weather conditions, in high mountainous terrain, in an area where there was a lack of radio navigation aids.

Finally, the NTSB purported that “a crash locator beacon, activated once the aircraft had crashed, would have provided an expeditious means of locating the aircraft.”

————————————–

Photo: by Bill Larkins

KenP

I can remember the week that this happened and the strong desire to find these people by many, many searchers. I remember the newspaper accounts of the compassion and concern to try and save the possible survivors.