|

Listen to this Gambling History blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1938-Today

Bets placed, spectators occupy the stands, waiting. Anticipation, excitement fill the air. Finally, the get-ready bell dings, and the crowd quickly quiets.

The start signal sounds. The gates open. Out lunge the competitors, into an immediate sprint. Hunting instinct kicks in. They deftly chase a single lure, sometimes a hare, unaware it’s fake.

Muscles in their lithe bodies bulge as they round the track. Their stride is wide, their motion smooth. They run as fast as 45 miles per hour.

In a flash, 30 seconds or so, they finish the lap. The winner is announced. Payouts are made.

This described activity, live dog racing as a gambling form, never really took off in The Silver State like it did in others, such as Florida and Oregon.

Today, it’s illegal, per Nevada Revised Statute 466. The law dictates that running such an operation is a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 and/or a jail term up to six months. Anyone with such a conviction also could be disqualified from obtaining or maintaining a gambling license. (Dog racing without gambling, that doesn’t violate any animal cruelty laws, is legal in Nevada.)

Maiden Races in Nevada

The first dog racing with gambling in Nevada took place in 1938 and 1939 at the Reno Speedway at Lawton’s Hot Springs just west of Reno. (The first dog track was built in the U.S. in 1919, in California.) Presumably, these races at Lawton’s were held illegally because existing Nevada laws that legalized gambling didn’t cover dog racing or optional betting. At the same time, no law specified either as being prohibited. With optional betting, wagerers purchased options on dogs of their choice, and winners redeemed their options for cash.

All was quiet on the Nevada dog racing front until 1947.

The Pot Gets Stirred

In September of that year, some Los Angeles-based promoters doing business as the Nevada Turf and Kennel Club applied to the Nevada Racing Commission for a license to conduct dog racing in Reno. Three members comprised the commission — Ernie W. Cragin and J.K. Houssels, in Las Vegas, who opposed dog racing, and Tom G. Wheelwright, of Ely, who didn’t.

The racing commissioners denied the permit for a few reasons. Primarily, they believed the applicants were more interested in the gambling element than the racing one. Also, commissioners declared dog racing to not be in Nevada’s best interest.

With the assistance of Reno attorney Douglas Busey, the race promoters filed a writ of mandamus that would make the racing commission grant them the license they’d requested.

Judge Merwyn Brown of Winnemucca heard arguments on the petition in December and announced his ruling two months later.

He determined the license denial lacked merit, given the commissioners had failed to provide any evidence to support their reasons for it. Brown stated, too, the commissioners had overstepped their bounds in that the question of whether dog racing was good or bad for Nevada was a public policy matter, and thus under the Legislature’s purview, not theirs.

Thus, Brown ordered the commission to issue a license to the Nevada Turf and Kennel Club, and in doing so, essentially declared dog racing with gambling legal.

Despite the green light, the license recipients never followed through with a track and races, for unknown reasons.

Pros and Cons

With the issue fresh in Nevadans’ minds, during the 1949 Nevada legislative session, the Senate introduced bill 103, which sought to ban dog racing by classifying it as a public nuisance.

Proponents of the measure claimed dog racing wasn’t clean (doping was prevalent), not established in The Silver State and without state laws to control it.

Opponents argued dog racing would bring more tourists to Nevada and increase much-needed revenue for it. At the time, dog racing was legal in eight states, including California and Oregon. At least four lobbyists from California aggressively sought to get the bill defeated. According to Nevada Assemblyman James Johnson (D.), White Pine County, some of their tactics were unacceptable.

“One of them even intimated to me that they didn’t have any money now but that if we killed this bill they might have some within a year or two and they intimated they might be able to pay off later,” Johnson said (Reno Evening Gazette, March 12, 1949).

Assemblyman Harry Claiborne (D.), Clark County, argued that allowing dog racing wasn’t worth any amount of money and if it was permitted, “you’re going to have in two years the biggest mess in Nevada that you’ve ever had with gambling” (Nevada State Journal, March 13, 1949).

Governor Vail Pittman signed SB103 into law in early April 1949. (Interestingly, while the bill added dog racing as a public nuisance, it removed prostitution as one.)

The Issue Revisited

Walking back its longtime stance on dog racing, the Nevada Legislature passed a bill in 1973 allowing greyhound racing but only in Henderson and only when held in conjunction with horse racing.

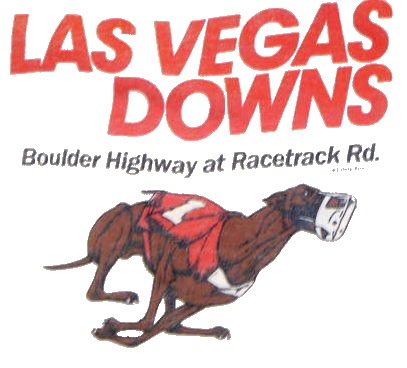

In December 1976, the racing commission granted a license to Las Vegas Downs Inc. to hold dog racing 200 days a year and horse racing, 100 days, once the track is built. The commission also waived the horse racing requirement for the first season.

In August 1977, the same agency granted David J. Funk & Associates a gambling license to manage the proposed (it still hadn’t been built) Henderson dog and horse race track. Funk and his family had lots of experience in this area, having run multiple dog tracks in Arizona.

Financing problems delayed dog track construction time and time again, but it finally happened in 1980. The track opened in mid-January 1981, offering daily racing and parimutuel betting.

For the second season, by law, the track had to be modified for horse racing, another expense, and it wasn’t done. This ended dog racing in Henderson.

No More Wavering

Starting in the 1990s, many U.S. states reversed their laws that legalized live dog racing plus betting. Nevada was the eighth state to do so. It lowered the final curtain on this gambling form in 1997. The pertinent statute, NRS 466.095 reads: “Issuance of license to conduct dog racing or pari-mutuel wagering in connection with certain dog racing prohibited.”

The law remains in effect today, nearly a quarter-century later.

—————————————–

Top greyhound photo: By Matt Schumitz, from Wikimedia Commons