|

Listen to this Gambling History blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

1936

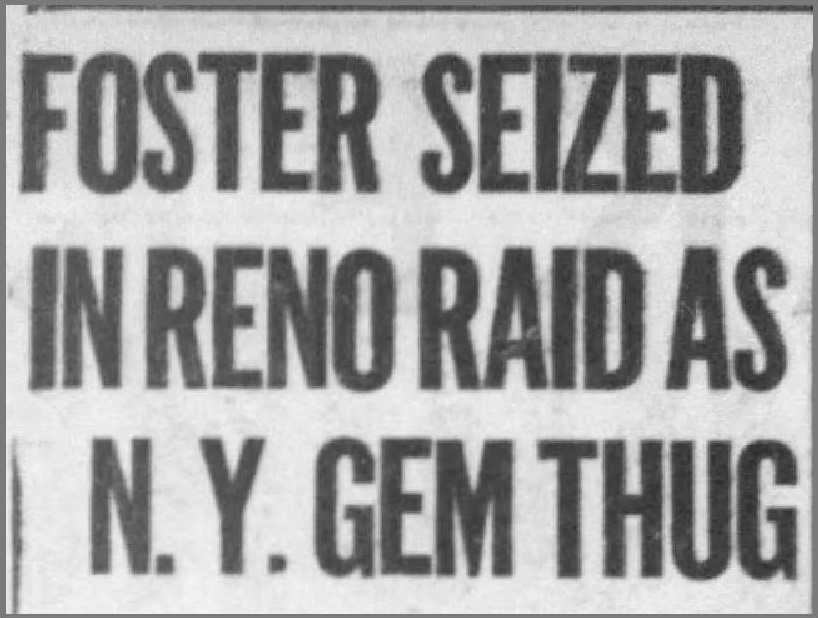

A man walked into the Greenleaf & Crosby jewelry store in New York’s Rockefeller Center at about 11 a.m. on Monday, January 6. Two others followed through the other entrance. “This is a stickup,” one of them said.

He ordered the two salesmen there, Walter Gibson and Robert Mercadal, to sit and not turn their heads. With the other person present, a colleague from another company, he had his accomplices bind, gag and handcuff him to a table leg in the back room.

The thieves took from the cases the most valuable diamond pieces — one, a pendant, was valued at about $35,000 ($652,000 today). The trio got away with about $125,000 ($2.3 million today) worth of merchandise.

After the six minute long robbery, Gibson and Mercadal identified Frank Frost, by picking his photo out of mugshot books, as being one of the robbers and the trio’s leader, the one who gave the orders.

The Law Comes A-Calling

Three months later, Reno, Nevada police arrested Frost at his home on April 8 and confiscated an unloaded revolver they found in his wife Dorothy’s room. Before Frost went willingly and unarmed, he telephoned Jack Sullivan, the manager of the Bank Club casino, owned by local gambler-Mobsters William “Bill/Curly” Graham and James “Jim/Cinch” McKay.

Sullivan, a close Graham and McKay associate, arranged for an attorney for Frost (William McKnight) and raised and paid his $10,000 ($186,000 today) bail. A now free Frost was to be taken to New York to answer to charges there, but detectives couldn’t find him. Frost had chosen to hide such so that could stay in Reno for an upcoming habeas corpus hearing* that his attorney had requested and, simultaneously, protect his bail and stay out of jail. After some clever legal moves, Frost turned himself in and, again, was released on bail.

A Constructed Alibi?

At the hearing start on Monday, April 20, Frost kicked off a parade of about 40 people who would testify on his behalf. In contrast, the state of New York would present a single witness. The defendant recounted what he’d done up to, including and after January 6, 1936, the day of the heist, in which he claimed he hadn’t been involved.

Frank Frost

January 4: According to Frost, he and Graham left Reno’s Grand Central Garage in the morning and headed to Sacramento, California. They put chains on their vehicle’s tires in Truckee and later removed them at Baxter’s Camp. Once at their destination, they hung out at the Equipoise Club and stayed the night at the Senator Hotel.

January 5: Frost and Graham visited the Capital Clothing Company, where Frost bought three hats and, later, the two bet on some horse races. In the afternoon, they set out for Reno, first stopping on the way at the Rainbow Tavern and later at the Soda Springs Hotel for dinner with two of Graham’s friends. There, Frost phoned Dorothy to check in. Back in Reno, the men drove to Graham’s house, where Dorothy was staying with Graham’s wife. The Frosts drove in Graham’s car to the George Wingfield, Sr.-owned Golden Hotel, their place of residence at the time.

January 6: Frost walked to the Riverside Hotel to pick up some papers and while there, ran into Charles Mayer, a mining prospector with whom Frost had visited various properties. The two discussed possibly meeting up later to take another trip. Frost then went to the Bank Club, bet on a horse named Tamalpais racing at Santa Anita and when it won, collected his winnings. Afterward, he received the lease on a house he and Dorothy were interested in and later discussed it with rental agent, Maurice Burman. At night, Frost, back at the Golden, played cards in the bar room, and chatted with two men.

January 7: Frost signed the lease at Burman’s office, paid two months’ rent and applied for phone and electricity at the house.

“Were you in New York on January 6,” McKnight asked him.

“No, sir,” Frost answered.

“Were you in New York any time after that?”

“No, sir.”

Graham testified next, saying he’d known Frost for years, having met him in New York. Frost had come to Reno in 1931 for the Baer-Uzcudun boxing match and, subsequently, the two met up a few times in San Francisco. Graham corroborated Frost’s account of their Sacramento trip and said he’d seen Frost at the Bank Club on January 6.

Next, six witnesses from California testified, at Graham’s request. He paid their expenses and even gave one an additional $20. The slew of others who took the stand collectively confirmed details Frost had testified to, and several reported having seen him at various times between January 4 and 7.

On the hearing’s third and final day, Gibson, one of the Greenleaf & Crosby salesmen, testified against Frost. He described the start of the robbery, saying, “I turned and faced him, and my eyes never left him. He directed me what to do — go over to a table and sit down,” he recalled (Reno Evening Gazette, April 23, 1936). Then “I was warned not to turn my head; what went on behind me was a matter of conjecture. My reaction [to the robbery] was not one of fear but was more of bewilderment— I was slightly stunned.”

When Gibson pointed out Frost in the courtroom, Frost interjected, “Look me in the eye when you say that. Look me straight in the eye.”

Gibson continued, “but it was apparent that he was very nervous. He spoke rapidly, and while he related his story, Foster continued to glare at the witness,” the Reno Evening Gazette reported (April 22, 1936).

After two hours of cross-examination by McKnight, Gibson looked right at Frost and said, “I know the man sitting before me is the man who came into the store that morning” (Nevada State Journal, April 23, 1936).

Judge Thomas F. Moran

The opposing attorneys presented their final arguments, and Judge Thomas F. Moran ruled. He made the writ of habeas corpus permanent.

“From the evidence introduced by some reputable citizens of Reno,” he said, “I am led to believe the petitioner was not in New York on the morning of January 6.”

“Frost’s extradition to New York was blocked by a habeas corpus procedure,” noted the Nevada State Journal (Sept. 11, 1953). “It was the first of several legal moves which in later years prevented numerous notorious figures from being returned from Nevada to other states to face criminal charges.”

Eventually, New York dismissed the charges against Frost. The federal government could’ve pursued the charge they previously had filed against him of fleeing across a state border to avoid prosecution of an alleged felony, but it didn’t.

Had Frost been involved in the robbery of Greenleaf & Crosby, he got off scot-free.

Shady Intervention for Frost

Seventeen years later, in 1953, Frost wanted to explain away to Nevada gambling regulators his prior arrests for carrying an unconcealed weapon and for the jewelry store robbery. Regarding the latter, he had in his possession a letter that Sullivan had obtained when recently in New York and, by happenstance, Cartier’s, the jewelry store where former Greenleaf & Crosby salesman, Gibson, now worked. The letter was written by Gibson and indicated when he’d identified Frost as one of the 1936 robbers, he’d mistaken him for someone else and was sorry for his error.

Frost explained to the Nevada State Journal that Sullivan, while in Cartier’s, mentioned he was from Reno, and this led to the subject of the robbery, Gibson volunteering he’d misidentified Frost and then him giving Sullivan the letter.

Underhanded Tit for Tat?

Why did Graham and Sullivan seemingly go out of their way to help Frost? Yes, they reportedly were friends, but the extent to which they went for Frost suggests something larger at play. Perhaps Graham and/or Sullivan had put Frost up to robbing the jewelry store. Maybe one or more people in the Reno Mobsters’ circle owed Frost, perhaps for one or more favors or unpleasant jobs he’d done for them.

Two mysterious events occurred in Northern Nevada that fit the timeline and that might’ve been the outcome of those favors.

Suspicious Vanishing of Key Witness

The first was the March 23, 1934 disappearance of Renoite Roy Frisch, who was to be the prosecution’s primary witness in Graham and McKay’s upcoming trial for swindling investors out of thousands of dollars via the mail. Frisch was the head cashier at Wingfield’s Riverside Bank, through which Graham and McKay had made their exploitive transactions.

The duo’s initial mail fraud trial resulted in a hung jury. (The two would be convicted in their third trial in 1938 and would go to the U.S. Penitentiary, Leavenworth in August 1939.) The prevailing theory about Frisch’s going missing is that “Baby Face Nelson,” né Lester Gillis, friend of Graham and McKay, killed Frisch and disposed of his body. Perhaps, instead, Frost had been the actual perpetrator. Murder seemed to be part of his criminal repertoire. In 1934, Frost allegedly had been living in Los Angeles at the time, an ideal cover for Frisch’s disappearance as Reno police wouldn’t have known about Frost and, thus, wouldn’t have suspected he’d been involved.

Sketchy Demise of Miner, Gambler

The other suspicious happening was the death of Reno resident Art Zeller, in his 50s, who never returned from a trip to meet up with Nevada prospector, Tom Dalton, and Dalton’s mining camp near Winnemucca Lake on March 16, 1936. Before he set out that Monday morning, he told Frank Golden, the manager of Wingfield’s Golden Hotel, where Zeller lived, where he was going and that he’d return in the afternoon. However, Golden didn’t notify police that Zeller was missing until 10:30 p.m. Thursday; by that time, he was dead already, it would turn out.

On Friday, Washoe County Sheriff Ray Root and others began searching for Zeller. They discovered his abandoned Buick about 500 yards northeast of Winnemucca Lake and noted its clutch was damaged. From there, they traced footprints, presumably Zeller’s, for 30 miles but lost the trail.

The sheriff discovered Zeller’s frozen body about 10 miles to the southeast of the lake on Monday morning. The lawman hypothesized that Zeller had gotten stranded in the deep sands, had begun walking southward but after a few miles, perhaps confused and/or lost, had started wandering, “the trail sometimes leading to the shore of the lake, and at other times far into the desert” (Reno Evening Gazette, March 23, 1936). Root calculated that Zeller had traversed about 55 miles on foot.

Among the expected items in his pockets — cash, car keys, notebook, etc. — was a small, unlabeled brown pharmacy bottle containing a few drops of amber-colored liquid. Had someone replaced his medicine with something that would render him confused or delirious or, worse, slowly take his life?

Though Root ruled out foul play and the coroner’s jury determined Zeller succumbed from exposure, his death didn’t make sense entirely. For one, he had several years of experience scouting out mining properties. Two, Dalton had given Zeller a detailed map of the route to his property, which included the mile count at every turn. Dalton also had warned Zeller about the sand, telling him his car had stalled in it two weeks earlier. Further, one could see the highway from the place Zeller’s car was found, Dalton said.

“If he had walked west for 17 miles, he would have gotten on the Gerlach Highway,” Dalton told the Reno Evening Gazette (March 27, 1936).

When Zeller died, Frost had been living in Reno for four months and hadn’t been arrested yet for the New York jewelry heist. Oddly, since the Chicago Mobster had moved to Reno, he’d taken regular trips to mining properties with Zeller’s partner, Charles Mayer. Why suddenly had Frost been so interested in mining?

When Zeller died, Frost had been living in Reno for four months and hadn’t been arrested yet for the New York jewelry heist. Oddly, since the Chicago Mobster had moved to Reno, he’d taken regular trips to mining properties with Zeller’s partner, Charles Mayer. Why suddenly had Frost been so interested in mining?

At the time of his passing, Zeller had been funding the excavation of a tunnel on the Manitouwoc property south of Quartz Mountain in Nevada’s Nye County. In the early 1920s, Wingfield, a miner, too, had expressed interest in Quartz Mountain after a new silver-lead discovery had been made there. That reportedly had led to a mad rush to the area, but mining had been short-lived because the deposit had been deemed shallow. Had Wingfield wanted Zeller out of the picture for some reason related to Manitouwoc or to mining?

Zeller also had been running roulette at Incline Village’s Cal-Neva Lodge, then owned by Graham and McKay and the casino run by Northern California Mobster, Elmer “Bones” Remmer. Police discovered a roulette wheel rigging device and a large opium supply in Zeller’s hotel room after his death. Had Zeller been murdered over something to do with gambling or drug dealing?

———————————————–

* A writ of habeas corpus, which translates in English to “produce the body,” is a court order mandating that an official, such as a warden but in this case, the Washoe County district attorney, deliver an imprisoned individual to the court and show a valid reason for their detention.

Photo from Pond5.com: Diamonds by ivan_kuprevich