|

Listen to this Gambling History blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Kepplinger Holdout on the body

1888

It was the “very finest … the world has ever seen … a masterpiece,” wrote John Nevil Maskelyne in his 1894 book, Sharps and Flats: A Complete Revelation of the Secrets of Cheating at Games of Chance and Skill.

It was the “most complicated, ingenious and successful contraption in the history of crooked gambling,” someone in the know said more recently, in the 20th century. He was Frank Garcia, or the “The Gambling Investigator,” who nationally exposed and demonstrated ways to cheat at gambling.

It was the Kepplinger Holdout, which came on the scene in 1888 in San Francisco, California. A holdout is a mechanical device that allows a person to “hold out,” or conceal, one or more cards, until the card player (or magician) wants to use one for a game advantage (or trick).

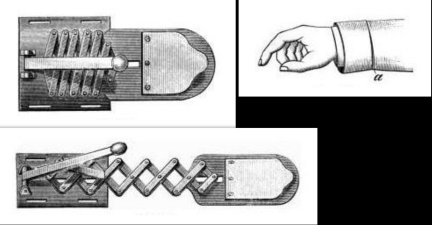

Jacob’s Ladder, closed and open; Cuff Holdout, a marking its opening

How It Compared

The Kepplinger, interchangeably called the San Francisco, was superior to previous holdouts for two critical reasons.

One, it worked flawlessly, without the typical problems of its predecessors, such as cards getting hung up in the cuff and string getting tangled in a pulley wheel.

Two, it “operated imperceptibly and invisibly,” G.R. Williamson wrote in Frontier Gambling. Users didn’t make any noticeable body movements when employing it, like pressing a forearm against the table, required with the Jacob’s Ladder or crossing one’s hands, which activated the cuff-pocket holdout. The Kepplinger was used with a special shirt, one with double shirtsleeves and cuffs, so that if someone peered up the user’s sleeve, they wouldn’t see anything.

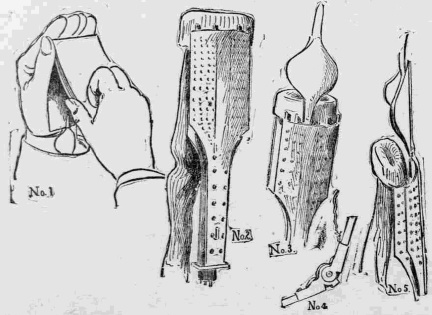

Original, Impeccable Design

The Kepplinger holdout consisted of wheels, tubes, strings, pulleys and other parts, all of which were connected and ran from the user’s knees to shoulders and down to a wrist, under their clothes. “The centerpiece was a metal slide attached to a rod, which retracted into a pair of steel jaws,” Williamson highlighted. The double shirtsleeves hid this assembly.

“The design was brilliant,” he added.

To activate the Kepplinger, in other words to secret away or return cards to one’s palm, the user spread their knees. This action, in the case of the former, caused the device’s steel jaws to open and the slide to extend. The user then inserted the card or cards into the cuff, and the jaws, securely holding them, closed — all undetectable by others. Click here for a video demonstration of how it worked.

Key parts of the Kepplinger Holdout

No. 1: Spring catch forced down into the hand to take away or deliver a card.

No. 2: Machine and, behind it, false sleeve as it rests on the arm when not in use.

No. 3: Arm part of machine and false sleeve, with the spring catch extended for use.

No. 4: Ingenious joint that allows the tubing to fit itself to motion of the body in all directions.

No. 5: Slide view of spring catch and holder showing double receptacle for taking away and delivering a card with one movement. The long tongue keeps the cards apart.

Man Behind the Machine

The Kepplinger Holdout was named eponymously after its inventor, P.J. Kepplinger, known in high-class Frisco gambling circles.

“[He] was a professional gambler; that is, he was. In other words, he was a sharp — and of the sharpest,” Maskelyne noted.

After creating the device, Kepplinger tested it for months in poker games with the other local card sharps. It proved infallible, as he won continuously and, thus, earned the nickname, “The Lucky Dutchman.” His opponents suspected he was cheating, though, but after ruling out all of the known methods, they couldn’t figure out how.

That is, until one day they cornered him and searched his person. Kepplinger reportedly put up a valiant fight but soon was overpowered. They discovered the machine.

Those men, whose money Kepplinger repeatedly pilfered deviously, didn’t want to hurt or even kill Kepplinger for his having cheated them. Rather, each wanted the device for himself!

The inventor’s secret was out. That meant a new revenue source for him but the end of an income that personal use of his innovation guaranteed him.

“The new holdout became common property of card sharps everywhere,” Williamson wrote. “By the 1890s, gambling supply companies were selling Kepplinger or San Francisco holdouts for $100 apiece” (at least $2,500 today). In 1930, the device still was being used; 21 player, Francis Leo Luckett, for one, capitalized on it in Reno, Nevada gambling saloons that year.

————————————-

X-ray image from A&E Networks’ History channel

Diagram from Washington D.C.’s Morning Times, May 17, 1896