1961-1966

1961-1966

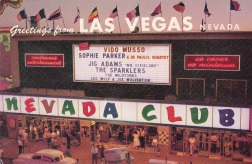

Early in 1961, Michael Catrone, 60, an apartment complex owner, presented to the Nevada Club in Las Vegas a winning keno ticket for $25,000 ($198,000 today). Yet the casino’s general manager didn’t pay it because it was suspicious — the ink on the ticket was lighter than on other ones.

An internal inquiry revealed a discrepancy between the machine-generated original and duplicate. The copies typically were locked up and used to confirm a winning ticket.

Catrone complained to the Nevada Gaming Control Board (NGCB) the gambling house had stiffed him. The casino’s owner, Robert Van Santen, went to the police, claiming Catrone had tried to cheat the house and hired a private eye to look into the incident. Law enforcement, the NGCB and the district attorney’s (D.A.’s) office investigated.

Concluding that Catrone and two Nevada Club employees — Robert Pearson, 27, and Stanley Wagner, 28 — had colluded to take the casino, detectives theorized the perpetrators had run a blank ticket through the keno machine, then after the winning numbers had been posted, had opened the machine and had marked those digits on the ticket. The D.A. charged the three with attempting to obtain money under false pretenses (the doctored keno ticket) by defrauding the club.

NGCB agents looked into the matter and after receiving a confession from Wagner, told Van Santen he didn’t have to pay the $25,000.

In the preliminary hearing, the prosecution tried to introduce into evidence Wagner’s written and signed confession of his involvement, but the defense objected, noting the Nevada Club had offered Wagner $1,000 in exchange for the confession. (Was this true?) Later, claiming the casino had only given him $250 of the agreed upon $1,000, Wagner retracted his previous admission of guilt.

Prosecution’s House Of Cards

D.A. John Mendoza pursued a case against the three, all of whom pled innocent.

During the trial, which began in April 1962, the prosecution’s key witness, Frank Cirinna, a bartender at the Log Cabin, testified that Pearson had approached him about participating in an illegal keno ticket scheme. Cirinna, however, lied on the stand about his meetings with Van Santen, asserting he’d only met him once informally. (Had Van Santen asked or paid Cirinna to testify as he had about Pearson?)

Despite defense attorney Harry Claiborne grilling him about meeting with Van Santen more than once, Cirinna stuck to his story. When Mendoza questioned him, Cirinna admitted he’d lied but wouldn’t say why, so the judge had him jailed for contempt. After several hours, though, the judge freed him.

John Baptist Pollett (aka Johnny Dean) a former friend of Wagner and an ex-convict out on bail at the time for a disorderly charge in Reno, took the stand for the prosecution. During his testimony, it came out that someone, Dean refused to say who (perhaps Van Santen or his P.I.), offered him $3,500 to get a confession out of Wagner for the Nevada Club’s private investigator. Dean claimed he never got the $3,500. (Had Dean gotten the money or not? Was Dean supposed to give $1,000 of it to Wagner for his confession but only gave him $250?)

While Dean was on the stand, Mendoza filed a motion to dismiss the charges against all three defendants, as Claiborne had discredited his two key witnesses, Cirinna and Dean, and he didn’t believe he could win solely based on two document experts’ testimony. He noted that Cirinna and Dean, while testifying, had divulged information that Mendoza hadn’t known when he’d filed the complaint against the defendants. District Judge Compton agreed with the motion.

Back To The Money

Following the ruling, Van Santen reiterated his refusal to pay the disputed $25,000 because “the trial had nothing to do with the validity of the ticket” (Las Vegas Sun, May 2, 1962).

Claiborne tried to get the NGCB to force Van Santen to pay, to no avail. Mandating that a gambling win be paid or not wasn’t part of the NGCB’s role, Chairman Ed Olsen said.

“Our function is merely to determine whether the circumstances are such as to warrant the board in proceeding against a club’s license for unsuitable method of operation on the basis of a failure to pay a gambling win,” he added (Las Vegas Sun, Oct. 27, 1962).

Catrone and his attorney pursued a different tack for getting the money. They sued Van Santen and his corporation for $750,000 in damages for false imprisonment and malicious prosecution.

District Judge George Marshall, however, handed down a summary judgment in favor of the Nevada Club. On appeal, the Nevada Supreme Court, in 1966, unanimously affirmed the lower court’s ruling.