Street photo of 2nd Street Reno in 1950, with Club Cal-Neva

In a likely unprecedented event, with all of the necessary equipment on hand, demonstrations of how a local casino operated its race horse keno game were provided to the judge and jury in a Reno, Nevada courtroom in 1950.

These presentations were part of the defense strategy during the three-day February trial regarding the civil court case, Leon Pierce v. Club Cal Neva.

Hedging His Bets

In his suit and when testifying in court, Reno resident and sporting goods store worker Leon Pierce alleged that the Club Cal Neva casino owed and refused to pay him $5,000 (about $60,000 today) for a winning race horse keno ticket he played in January 1949. Pierce claimed that the 10 horse numbers he chose to be winners, on a $1 ten-spot ticket, actually were. Pierce was the only witness for his side.

(A similar case involving plain, not race horse, keno would happen a decade later at the Nevada Club in Las Vegas.)

Going for the Win

The Club Cal Neva and its defense team sought to prove that Pierce’s keno ticket had been filled out after the winning race was called. They alleged that Pierce’s ticket had been for race number 126, as shown by his receipt, but the winning race had been 127. For some reason, his marked ticket was in the pile of tickets for 127 not 126. Because Pierce’s ticket was for a non-winning race, the casino didn’t owe him any payout, its attorneys argued.

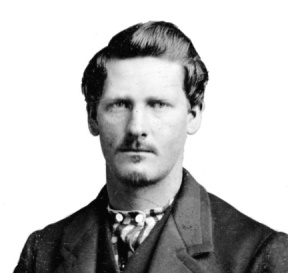

To help jury members understand, Club Cal Neva casino manager Samuel “Sam” A. Boyd* explained the bookkeeping and other operations of race horse keno, using the game implements brought into the courtroom for this very purpose. He showed how tickets were written and payoffs were made.

He said the ticket mixup could’ve been the dealer’s fault or an incidence of Pierce “capping the book.” If the latter, Pierce likely distracted the dealer and slipped a blank race 126 ticket on top of the blank tickets for race 127 then asked him to write a ticket for him. The dealer grabbed and filled out the top ticket.

The Double Whammy

The defense presented two additional witnesses. The first was Emmet Shea, a former, local race horse keno writer now living in Montana. Shea testified that when he’d worked at Harolds Club previously, Pierce had asked him two different times whether he’d be willing to collude with Pierce to produce a winning ticket.

“I told him he was nuts,” Shea testified (Nevada State Journal, Feb. 17, 1950).

Shea added that some time after that, when he’d managed keno for the defendant, he’d instructed his writers to ban Pierce from the game.

Next up on the stand was Rudy Stanch, a current Club Cal Neva employee. He said that in July 1949 Pierce had offered him $200 to testify in court that his employer had operated keno illegally. Stanch said he’d refused.

On cross-examination, Pierce denied all of the witnesses’ allegations. He didn’t know how his ticket wound up in the wrong pile, he said.

Out of Luck

The jury, comprised of seven women and five men, deliberated the case for about two hours.

The verdict was in favor of the Club Cal Neva. Ten jurors voted for the casino, one voted for Pierce and another voted for neither side (civil suits didn’t require a unanimous jury vote).

What do you think about this case? Did Pierce have a legitimate claim or was he trying to scam the casino?

———————————

* Sam Boyd went on to co-found Boyd Gaming and grow it into one of the world’s largest gambling empires. The stadium at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas is named in Boyd’s honor.

Mike M

The was a crook and slipped the ticket on top. They should have arrested him for cheating.

Doresa Banning

Hi Mike,

It certainly seems like that was the case. Thanks for your comment!

Doresa