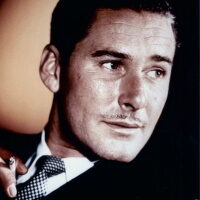

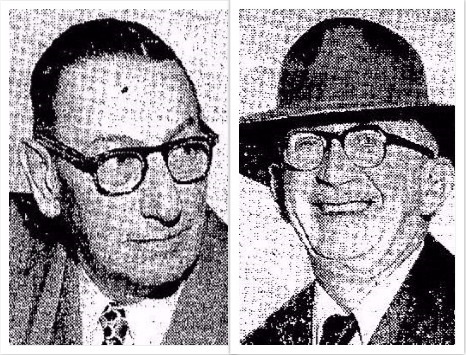

Bill Pechart, left, and Dave Kessel

1950-1953

During the 1950 federal hearings on organized crime, two Northern California gamblers — Walter “Big Bill” Melburn Pechart and David “Dave” Nathan Kessel — were uncooperative, according to the questioners.

They were Senators Estes Kefauver (D-Tenn.), Charles Tobey (R-N.H.) and Alexander Wiley (R-Wisc.), congressmen who comprised the Kefauver Committee, or the United States Senate Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce. During its two-year probe, the group conducted inquiries in 14 major cities across the nation, during which more than 600 individuals testified.

In San Francisco, the committee subpoenaed Bill Pechart and Dave Kessel to testify because they were “big wheels” in illegal gambling along with bookmaking and slot machine enterprises in Contra Costa County, or the East Bay, as described in California Crime Commission reports.

During the 1930s and 1940s the partners owned and operated numerous illegal gambling clubs — including The Wagon Wheel, the 21, the Rancho San Pablo and the Hollywood — in the then-unincorporated area between El Cerrito and Richmond dubbed “No Man’s Land.” They also were former associates of Elmer “Bones” F. Remmer, co-owning at least one gambling house and allegedly bribing politicians to let them operate outside the law.

During those decades, California prohibited all types of gambling except draw poker (legalized in 1911) and horse racing (legalized in 1933).

One-Sided Sessions

At the start of questioning, Kessel, 56, read a statement indicating he wouldn’t answer questions because of potential self-incrimination. He claimed he’d written the verbiage but when asked the meaning of some of the included legal terms, he admitted his lawyer had penned it. Thus, the committee charged him with perjury. Subsequently, he answered nary a question, including whether or not he knew Pechart.

Kefauver described Kessel as “one of the most sinister characters” the committee had interviewed (Oakland Tribune, Nov. 22, 1950). “Very substantial charges as to his operations in Contra Costa County have been made by citizens of that area. He appears from these charges to be a nuisance and a very bad influence.”

Pechart, 57, responded to some queries but invoked his Fifth Amendment right on others, particularly those about the duo’s businesses, income and taxes.

Consequently, the committee cited both men for contempt of Congress, which the Senate subsequently officially affirmed. Kessel was indicted for refusing to answer 32 questions, Pechart for 38.

If convicted, each gambler faced a maximum of one year in prison plus a $1,000 fine for each question they refused to answer: $32,000 for Kessel, $38,000 for Pechart (about $328,000 and $389,000 today, respectively).

Ruling On Contempt

After having pleaded innocent in 1951, the two gamblers went to trial in January 1952.

They were acquitted.

“Taking the whole record and the setting and circumstances in which the questions were asked, there was a right to claim the privilege,” said Federal Judge Louis E. Goodman. Yes, Pechart and Kessel were engaged in illegal gambling and racketeering, but no one can be forced into being a witness against himself.

Goodman also found Senator Tobey to be hostile at times during questioning, which could’ve contributed to Pechart and Kessel fearing possible prosecution based on any information they might’ve provided.

In one instance, Tobey had asked: “Why in hell didn’t you come clean? When we get through with you, you will wish you had” (Oakland Tribune, Jan. 31, 1952). Another time, the senator had said, “You realize the penalty of breaking faith with this committee. It means a prison sentence.”

“There can’t be the faintest doubt that there was a reality of danger,” Goodman said about the hearing atmosphere, which lacked “impartiality” (Reno Evening Gazette, Jan. 30, 1952).

Kefauver, however, stated there was “no possible excuse” for the gamblers, “two of the most contemptuous witnesses who appeared before our committee,” not having answered questions (Oakland Tribune, Jan. 31, 1952). “It is a great disappointment and very discouraging that they were acquitted of the contempt charge.”

How About Nevada?

Six months after winning their contempt case, Pechart and Kessel tried to enter gaming in Reno, when they applied for a gambling license to run the Palace Club. They claimed to have given up all of their Northern California clubs in 1950. The Nevada Tax Commission, which then granted such permits, denied the men one due to their criminal background.