|

Listen to this Gambling History blog post here

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

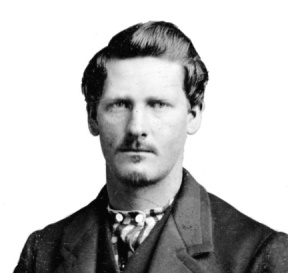

Cadell

1947-1950

Starting in 1947, Wiley “Buck” H. Cadell used his governmental position to build a statewide system of protection for illegal gambling operations in California, the first such concerted effort of this kind in the state. At the time Cadell worked as a gambling investigator, and previously an undercover agent, for California Attorney General Frederick N. Howser. Prior to that, he worked for 20 years as an officer for the Los Angeles Police Department.

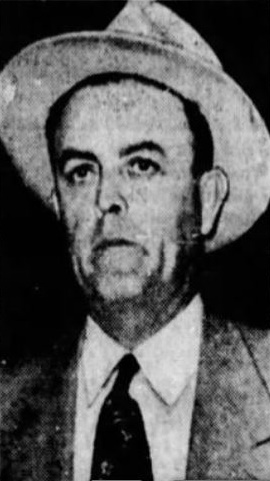

Howser

Howser was in on (and perhaps the mastermind of) the conspiracy. His role was covering it up and shielding Cadell and his other agents — Charles Hoy and Walter Lentz — from external investigation and prosecution.

Hoy

Lentz

How It Worked

One part of setting up the protection racket involved getting all of the gamblers in a county to pay a monthly fee or close shop. In exchange, law enforcement wouldn’t interfere with their illegal business.

From gambling house owners, the colluding agents demanded anywhere from 20 to 50 percent of their enterprise’s gross earnings. For slot machine operators, the fee was $4 apiece. For punchboard users, it was $2. (A different group of men was involved in organizing a punchboard monopoly and protection system in The Golden State. They, too, did this with Howser’s blessing.)

For the protection scheme to work, the conspirators also had to get the police chief or sheriff in the same county on board. This meant the officers of the law had to agree to ignore the commercial gambling happening in their jurisdiction. For doing so, they’d receive a portion of the collected payoff monies. Another part of the graft went to Howser.

To sway these law enforcement heads, Howser’s representatives emphasized they had powerful friends in Sacramento. They even often outrightly stated they “had the approval and the authority of the attorney general’s office,” the California Crime Commission reported in its Final Report (Nov. 15, 1950).

Progress Made

Howser’s agents worked on expanding the scheme for over a year. During that time, they approached many of California’s counties. The crime commission knew of at least 16, including Los Angeles, San Luis Obispo and San Bernardino. There may have been more.

Unraveling Begins

Cadell’s involvement ended in June 1948 when he was indicted for related activity (and thus, quit working for Howser). The ensuing charges were for organizing a slot machine protection racket and for plotting to bribe Mendocino County Sheriff Beverly Broaddus.

Howser publicly announced he fully supported Cadell. The elected official also claimed the charges against the agent had been trumped up to frame him.

Despite the AG’s position, a jury convicted Cadell (and two others, a former police officer and a resident, both of Los Angeles), each on five counts of bribery and gambling conspiracy. The judge sentenced Cadell, whom he identified as the “arch conspirator,” to three consecutive prison terms (The Modesto Bee and News-Herald, Dec. 18, 1948). They were 1 to 14 years followed by another 1 to 14 years and, lastly, 1 to 3 years.

“This was not a case of operation of an isolated slot machine,” the judge told the defendants, “but the crimes with which you are charged are more serious, about as dastardly as any crimes that are committed” (The Modesto Bee, Dec. 18, 1948).

As for Howser, no irrefutable evidence linked him to the payoffs. However, “he was tainted by the association,” author Ed Cray wrote in Chief Justice.

Impact of the Unwilling

Not every person Howser’s men approached on both sides, law enforcement and gambling, was keen on the scheme. Some rejected the proposal outright.

One gambler, Tiny Heller, an Alameda County bookmaker, refused to pay any graft. He was told by a member of the protection racket, Mobster-gambler Dave Kessel, that he could keep operating through the end of the football season but not afterwards. Heller continued taking bets. Soon after, before the deadline to close that Kessel cited, Heller’s business was raided, and Hoy arrested him.

Many other targets filed complaints or informed the crime commissioners about various people having tried to recruit them into the scheme. The crime agency detailed and published all such reported events in its 1950 report.

That exposure, combined with Cadell’s conviction and Howser’s failure to get re-elected in 1950, caused the system to crumble.