1932-Today

Though local, state and federal authorities were working to eradicate all gambling ships moored off of the Pacific Coast, the S.S. Monte Carlo met its demise at the hands of an unexpected interloper, Mother Nature.

On a Stormy Night

On New Year’s Eve in 1936, the waterborne casino, closed for the winter, offshore of San Diego, California. Only two caretakers, John Miller and John Gillespie, remained aboard.

“Southern California’s weather turned bad,” described Ernest Marquez, author of Noir Afloat. “Snow fell in the mountains, unrelenting rains turned hillsides into mudslides, gale-force winds toppled trees, and small craft warnings went up all along the entire Southland coast. Around the big Monte Carlo the sea churned and heaved. Waves 12 feet high pounded her hull. Around 3:30 a.m. … the Monte Carlo’s anchor chains, stressed to the breaking point by the power of the storm, snapped. She began to drift helplessly.”

The gambling vessel, her hull split in two, came to rest in shallow water close to the shore, about 200 to 300 yards from the beach, south of the Hotel del Coronado.

“With its first impact against the beach, the ship’s wooden superstructure which had housed the dining and gambling rooms began to crumble, and the high waves which swept over her soon began washing the timbers and furnishings up on the beach,” reported the Coronado Journal (Jan. 7, 1937). “The entire forward part of the superstructure was pounded to pieces by the waves, littering the beach with lumber, chairs, tables, roulette wheels and miscellaneous furniture.”

The shipwreck immediately drew hordes of people, who began taking items from the scene. Police arrived, confiscated the slot machines, crap tables and other gambling equipment and prevented any further scavenging. Removing “goods from any stranded vessel, or any goods cast by the sea upon the land” was illegal per then Section 545 of California’s Penal Code, a misdemeanor, punishable by an up to $500 (about $9,100 today) fine or six months’ jail time.

“The ship appeared to burrow its prow deeper in the sand with each pounding wave, and it was evident that it would be impossible to float her,” noted the Coronado Journal.

Her Storied Past

The Monte Carlo began as the Old North State during construction as an oil tanker in North Carolina in 1921. Unlike most other similar ships, her hull was reinforced concrete, part of a U.S. federal program to build such vessels out of materials other than steel. Old North State spanned 300 feet in length and 44 feet in width. Once put into service with the U.S. Quartermaster Corps, she became Tanker No. 1.

In 1923, the San Francisco-based Associated Oil Company bought her, renamed her McKittrick and put her into service.

Nine years later, two men, Ed V. Turner and Marvin “Doc” Schouweiler, acquired and converted her into a gambling ship. This involved, in part, adding a newly constructed wooden structure to house gambling and dining and filling the ship with cement to minimize the impact of movement. After the owners towed and anchored her three miles out to sea from Long Beach to be in federal waters, they debuted the S.S. Monte Carlo as “the world’s greatest pleasure ship,” via a grand opening on May 7, 1932.

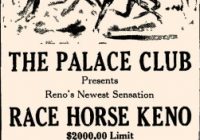

The casino featured craps, blackjack, roulette, chuck-a-luck, Chinese lottery, poker and slot machines as well as wagering on boxing matches and horse and dog races.

“Dice were either weighted or edged to increase the house odds, and were etched with the name of the ship,” wrote Joe Ditler (March 10, 2014).

During the offshore gambling era, between 1927 and 1939, vessels offering this activity and located off of the California coast included the Johanna Smith, Monfalcone, Rose Isle, Tango and Lux.

After about four years of various city and state law enforcement agencies trying to shutter the engine-less Monte Carlo for good, via raids, arrests and other efforts, the co-owners moved the asset to offshore San Diego in 1936.

After the Wreck

It’s unclear who was responsible for the floating casino when nature’s forces destroyed it, whether or not Turner and Schouweiler had sold it in the interim. No one came forward to claim it, suggesting Mob involvement.

“While the entire operation is traced to gangster, bootlegger and gambler Tony Cornero, the presence of Al Capone in Coronado at that time raises speculation that he either had a stake in the gambling ships, or wanted to,” Ditler wrote.

The City of Coronado, which lacked jurisdiction, attempted to get the Monte Carlo’s remains, deemed hazardous and unsightly, removed. Already a man had died, drowning while swimming out to the wreckage on the afternoon the craft had gone aground. (Over the ensuing years, several more would die similarly.)

The U.S. government refused to remove the Monte Carlo’s vestiges because they weren’t a “menace to general navigation,” the Coronado Journal (Feb. 4, 1937) reported.

Instead, “she slowly sank into the sand and was eventually buried,” Marquez wrote.

But she wasn’t entombed for good. Since and still today, when the conditions are right — super low tide after a winter El Niño storm — a weather-thrashed, dilapidated Monte Carlo emerges from her sandy grave. It’s as if she’s imploring us to not forget her and what she represents: a unique, controversial, decade-long trend and, thus, period, in U.S. gambling history, that of vast, bustling floating casino enterprises in the Pacific Ocean.

Have you seen what’s left of the S.S. Monte Carlo? We’d love to hear about it.

———————————-