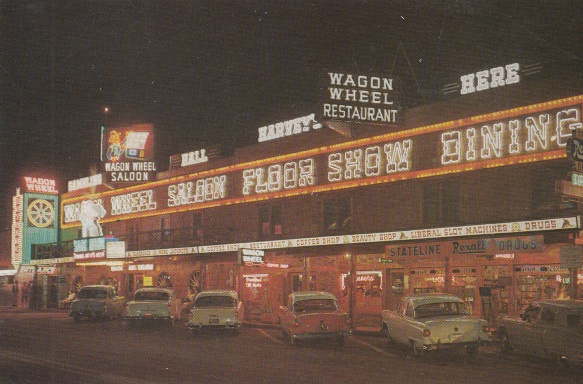

1957-1960

In June 1957, a federal grand jury secretly indicted the owners of the Wagon Wheel Saloon and Gambling Hall (Harvey’s today) at Lake Tahoe in Stateline, Nevada — Harvey A. Gross, and his wife, Llewellyn — for failing to pay more than $45,400 (about $395,500 today) in joint income taxes over a three-year period.

YEAR ACTUAL NET INCOME FILED NET INCOME ACTUAL TAX DUE TAX PAID TAX SHORTAGE

1950 $67,964.02 $26,905.53 $30,134.50 $6,558.60 $23,575.90

1951 $51,657.11 $42,755.92 $20,586.26 $15,336.88 $5,249.38

1952 $99,945.32 $77,069.60 $56,335.54 $39,742.24 $16,593.30

This wasn’t Gross’ first charge of evading taxes. Four years earlier, he’d been arrested for evading $500 ($4,600 today) in federal liquor taxes. The federal government said the former and current counts indicated a pattern of tax evasion; Gross’ attorneys described them as a series of government harassment of their client.

A Compelling Tale

The way the income tax story played out is filled with twists:

1) Three months after the indictment, Gross, age 52 at the time, sued a former bookkeeper, Lee Alvin Dorworth, and a Nevada-based Internal Revenue Service (IRS) agent, E.O. Draper. Gross alleged that Dorworth, who’d worked for him a decade earlier, had stolen from the Wagon Wheel a small notebook, a memo book and two ledger sheets containing financial casino records when Gross had fired him in July 1948 and had given them to the tax agency. In the suit, Gross asked for return of the items and $50,000 (about $435,600 today) in damages.

In December, a federal judge ruled the IRS had the right to examine and copy certain financial records allegedly taken from the business via clandestine means. Gross withdrew the lawsuit.

2) During the income tax trial, which got underway in March 1959, Gross’ lawyers presented a defense of shoddy accounting on the part of an employee (not Dorworth mentioned above).

3) At one point in the legal proceedings, Gross’ wife collapsed, supposedly from the stress of it all, and needed assistance leaving the courtroom.

4) At the request of attorneys on both sides, Judge Sherrill Halbert declared a mistrial because the transcript of testimony supposedly was “inaccurate, incomplete and inadequate,” containing more than 200 errors and omissions (Reno Evening Gazette, March 18, 1959). A new trial date was set for September.

5) The court reporter, Marie McIntyre, who’d had the job for 14 years, told the media her transcript didn’t contain any mistakes, never mind 200 of them — a “ridiculous” claim, she said (Reno Evening Gazette, March 19, 1959). She added that the judge had told her in confidence the transcript was fine, but later, when asked whether he’d said that, he denied it.

6) In June, Gross entered a nolo contendre, or no contest, plea to the tax evasion to end the saga, which he said had made his wife terribly ill. (She would die six years later, in 1965.)

7) Whereas many casino owners have done prison time for tax evasion, Gross escaped that specific sentence. Instead, Halbert fined him $20,000 ($168,000 today), to be paid back within the next five years, put him on probation of the same duration and ordered him to pay all of his outstanding back taxes plus the court costs. As for Llewellyn, Halbert dismissed the charges against her.

“I will look with strong disfavor,” Halbert warned, “on any technical plea … to attempt to avoid adjudication. You must pay your taxes as any other citizen.” … The “sloppy bookkeeping” excuse was flimsy and wouldn’t be allowed again, he added (Reno Evening Gazette, Oct. 5, 1959).

8) In January 1960, based on Gross being “adjudged convicted” in the tax case and after the Nevada Gaming Control Board’s (NGCB) investigation, the agency recommended the gaming commissioners revoke the Wagon Wheel owner’s gambling license on the grounds he was “unsuitable” for running a casino in the state. However, in August, the ultimate arbiters, the Nevada Gaming Commission, in opposition to the NGCB’s stance, allowed Gross to keep his gambling permit.

Decades in Business

The Wagon Wheel, which the Grosses had opened in 1944, would eventually be branded Harvey’s and remain under the family’s control, even after Harvey’s death in 1983, until 2001, when the Harrah’s corporation would acquire it.